I came to demography late in life. My first interest was in English – literature and language – and cultural studies. I knew that was what I wanted to study from a young age, and I was lucky enough to be offered a place at Jesus College Cambridge. One of my teachers there was Professor Raymond Williams. He was the son of a railwayman, grew up in the Welsh borders, had a strong affinity for working class life and values, studied at Cambridge, taught for Oxford university’s ‘delegation for extra-mural studies’ closely associated with the Workers’ Educational Association, before having an academic career in Cambridge. He managed to bridge the gap between traditional Cambridge literary criticism, Marxist approaches, and some of the modern theories emanating from continental Europe. He was also, in my experience, a very good teacher, approachable and supportive.

One of his books was Keywords: A vocabulary of culture and society (1976), which explored, explained, deconstructed important words in the field of cultural studies. Words such as culture, class, industry, intellectual, society featured, starting with their derivation, whether from latin, greek, or old norse. The layers of meaning, sometimes contested, sometimes contradictory, were revealed. The effect of the whole book was to understand the vocabulary of Williams’ intellectual model, and (from the perspective of a nineteen year old undergraduate) to acquire instant erudition.

My copy of ‘Keywords’ purchased 1977 as a first year undergraduate

So what of “demography”? I start as Williams did with the Oxford English Dictionary, which states that the origin of the word was a borrowing from Greek with an English element. Its primary definition is given as: “the study of human populations, especially the study of statistics, such as numbers of births and deaths, the incidence of disease, or rates of migration, which illustrate the changing size or composition of populations over time.”

δεμοσ [demos] + GRAPHY an abstract noun of action or function, the first cited example of its use was as a conscious neologism from the Transactions of the Provincial Medical and Surgical Association in 1834, “were it desirable to invent a new name, perhaps Medical Demography would be more appropriate, when applied to a thickly-peopled district”. The next example from the Library of Universal Knowledge in 1880 also focuses on the medical dimension: “the statistics of health and disease”. These early examples, and the definition they support continue to describe accurately a core meaning of demography – its focus on births, deaths, migration, population size and composition, its close relationship with statistics, etc..

A second definition is given as “the composition of a particular human population”. First example from the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1837, “These inscriptions throw light on the Demography of Attica”. Second example, from Norway: Official publication for the Paris Exhibition in 1900, “good and abundant material for the study of the demography of our country.”

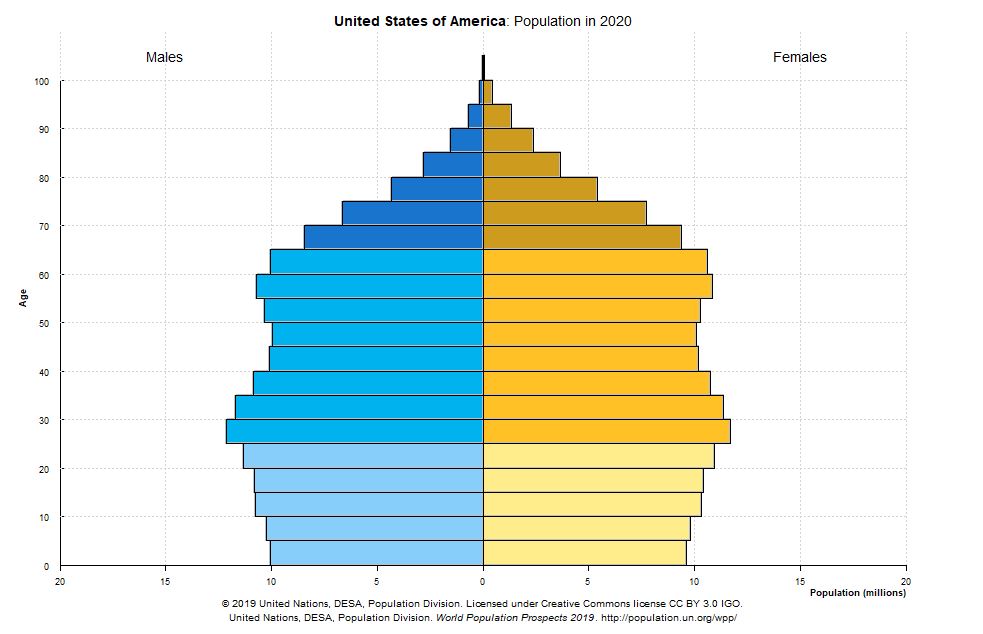

These two definitions, closely linked, echo two distinct meanings of statistics (a scientific methodology for the analysis of data, and the data itself). So “demography” is a scientific discipline with its own methods and devices, such as life tables, population pyramids, and agreed formulae for calculating key summary measures. It is also used to describe the population itself – “Germany has an ageing population.” “Fertility rates in sub-Saharan Africa remain high.” “University cities have high in- and out- migration of young people.”

A further definition extends the meaning of demography to the analysis of plant and animal populations – somewhat in contradition of the Greek demos – however the methodologies are clearly transferable to any population where members come into existence, move about, and ultimately die.

Let us move to “demographic”… it clearly shares the same origin, and is often used as the adjective associated with “demography” – as in “demographic methods”, but it also has a somewhat distinct meaning in relation to the description of sub-populations. The OED locates this latter meaning originating in the USA as a noun – “a particular section of a population, typically defined in terms of factors such as age, income, ethnic origin, etc., especially regarded as a target audience for broadcasting, advertising, or marketing.” An example of this use is cited from Billboard in 1972 “in trying to project a younger demographic, they wind up playing the Osmonds, the Partridge Family. What you see at that point is a mass exodus of listeners.” Or in Vancouver in 1992: “The new Chinese demographic: wealthy, sophisticated middle class expats who still insist on the quality they enjoyed in Hong Kong.”

So there are two broad groups of meanings “demography” as a science, focussing on fertility, mortality and migration – with various detailed methodologies, often close to national or international statistical agencies, supporting development activities, measuring the success of health interventions, etc. and “demographics” as a noun – a marketing concept intended to subset a population into groups who can be sold differend goods and services, advertised through different media.

My personal observation is that “demography” – as a science – is not well understood by non-specialists, even well educated ones; but “marketing demographics” is quite a familiar concept to many people. Perhaps those of us who are more affiliated to “demography” need to do more to promulgate our science and its headline findings?

Views and comments would be welcome.

The work of Raymond Williams on “keywords” is celebrated and preserved on the Keywords website, jointly maintained by Jesus College Cambridge and the University of Pittsburgh: https://keywords.pitt.edu/williams_keywords.html