People in England and Wales move around quite a lot, which makes them hard to count, and makes it hard to forecast how many will be where in the future. The age at which people are most likely to migrate between local authority districts is 18 – by quite a big margin. 18 is the age at which individuals acquire most of their adult rights and responsibilities. It is also the most common age for enrolment into university for undergraduate degrees. Whilst some young people are able to continue to live in their family home and travel to a local institution, many choose to move away from home. The social opportunities of going to university, as well as the educational opportunities, are strong motivators. It is, for most, a partial transition. Many students will return “home” for the holidays, and maybe some weekends. They will often retain a circle of friends in their home town, they may keep their bedroom at home, and still have a sense of ownership of their pet dog, which is now walked by their middle aged parents. Not so long ago it was statistical convention that they be recorded as resident at their parents’ home, but for some time now the convention has been to regard them as resident in their university district – clearly in respect of some public services they have an impact in both places.

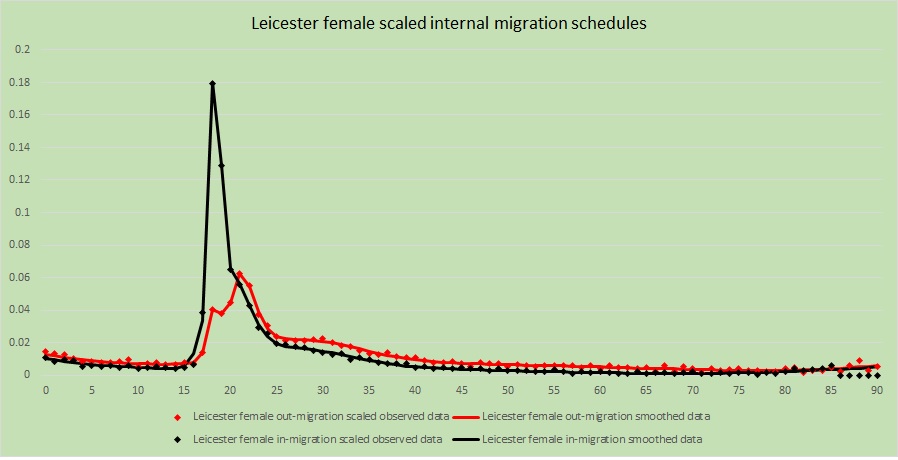

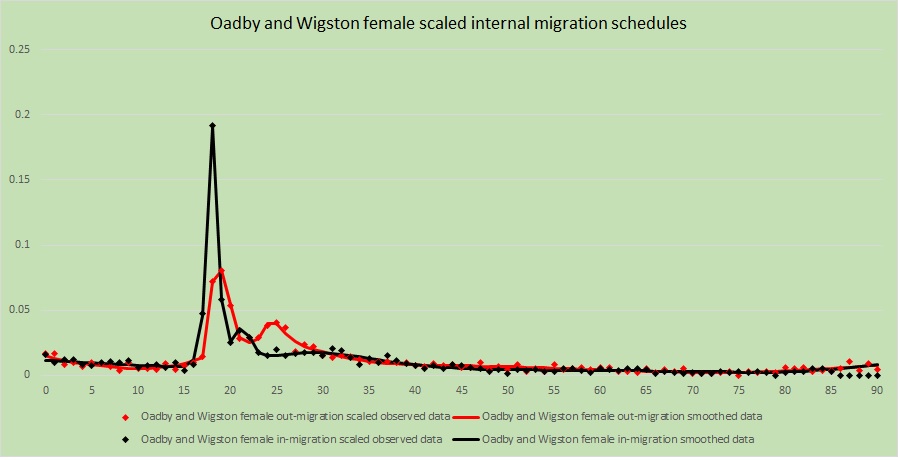

Whilst not all undergraduates start their studies at 18, the large majority do – hence the visible out-peak at that age in every local authority district. There is, of course, a corresponding in-peak in university districts. In districts dominated by higher education institutions, this is particularly marked. When I began my investigations I was surprised to find in-peaks in districts that I had not associated with universities: Oadby and Wigston (a suburban satellite of Leicester), Vale of White Horse (a rural and suburban district west of Oxford), and Broxstowe (an area of small mining towns and villages west of Nottingham). On investigation theses all proved to be districts where student halls of residence attached to the neighbouring university cities were located.

A typical residential trajectory for a student in England and Wales is from home to hall of residence at age eighteen, then to private rented accommodation the following year. This provides a gradual transition for the student (and the anxious parents). The hall of residence is likely to benefit from some supervision by the university and students’ union. It often provides a catering service, and deals with aspects of cleaning, repairs, etc.. Students usually live in single rooms within flats where there is some communal space including a kitchen. So the transition from being a dependent minor, to a (somewhat) independent adult is eased. By their second year students often move to a different type of accommodation. Sometimes this can be private sector student apartments (not dissimilar to halls of residence), or the “student house” – a normal residential house, often a Victorian terrace house, or a 1930s semi, where students live together in small groups, with very little supervision and much greater independence, both from parental and university control. Typically these student house areas are more urban than the halls of residence areas – so from leafy Oadby and Wigston to Leicester, from Vale of White Horse to Oxford city, from Broxstowe to Nottingham. This can produce a strong single year peak of migration as students move from one district to another – even if it is only a mile or two. (The resulting schedules of migration between Leicester and Oadby and Wigston can be seen in my post of 1st January 2020 “A Year of exciting demography ahead”.)

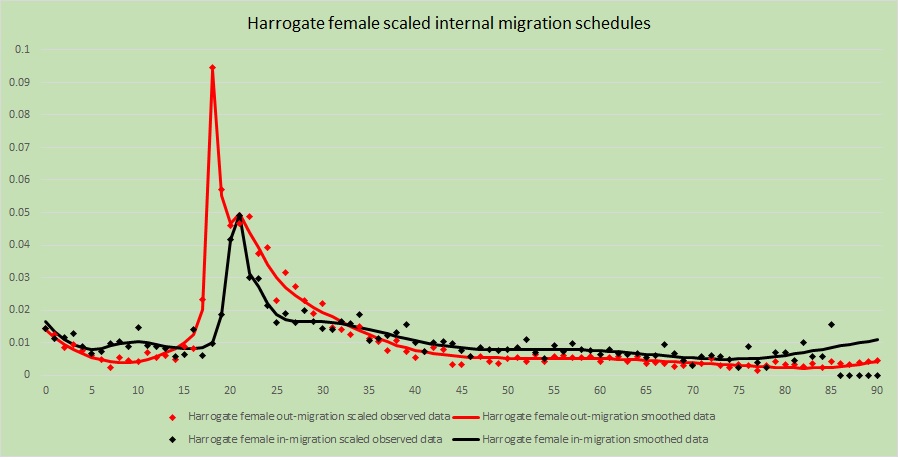

Most districts show an in-peak at 21 – likely to be graduates returning “home” after university, plus graduates taking up employment. The following example is from Harrogate, an attractive spa town in North Yorkshire.

The English and Welsh education systems are strongly structured by age. Children are obliged to be in full time education from the term after their fifth birthday. For most this means school, and it is usual to start in a “reception” class the year before as a four year old. Schools and local education authorities tend to be resistant to educating children outside their chronological age group, and will often only do so with the support of a (hard to obtain) recommendation from an educational psychologist. This means that children move through the school system in age cohorts, transferring from primary to secondary school the September after their eleventh birthday, and moving from statutory secondary education to slightly less statutory “sixth form” or further education at 16. Nearly all young people finish their schooling in the year of their eighteenth birthday, and for those that are going to move on to higher education, 18 is the most likely age to make that transition.

For the modeller of age schedules of migration this presents as challenge: we often want to remove noise – random age to age fluctuations in migration levels – but these sharp single year peaks are not noise, but signal. Childhood migration extends over several years, and can often be modelled as a negative exponential curve, and retirement migration is a phenomenon that can be observed as a shallow hump over the years of later middle age and early old age. However the education driven migration curves often focus on just a single year. Another phenomenon in England which applies to a small number of districts is the “public school peak” observed at age 13 amongst boys.

A public school in England is not a state school, but rather a fee-paying independent school, often established many hundreds of years ago. The most famous include Eton, Harrow and Winchester. The small district of Rutland, England’s third smallest district by population (just below 40,000) has a public school in both of its towns: Oakham and Uppingham.

A marked in-migration peak can be seen at age 13 as boys arrive at the two public schools. The height of the out-migration peak at 18 is likely to be enhanced by the two schools, as their pupils go to university, or return to their family home – either way almost certainly leaving Rutland. Modelling these peaks is clearly essential.

So, in conclusion, migration schedules in England and Wales requires modelling phenomena that extend over a range of age groups, and single year peaks, most often associated with educational institutions where there is a residential component. It would certainly be a mistake to regard these peaks as “noise” to be smoothed out. They are an important part of the signal.